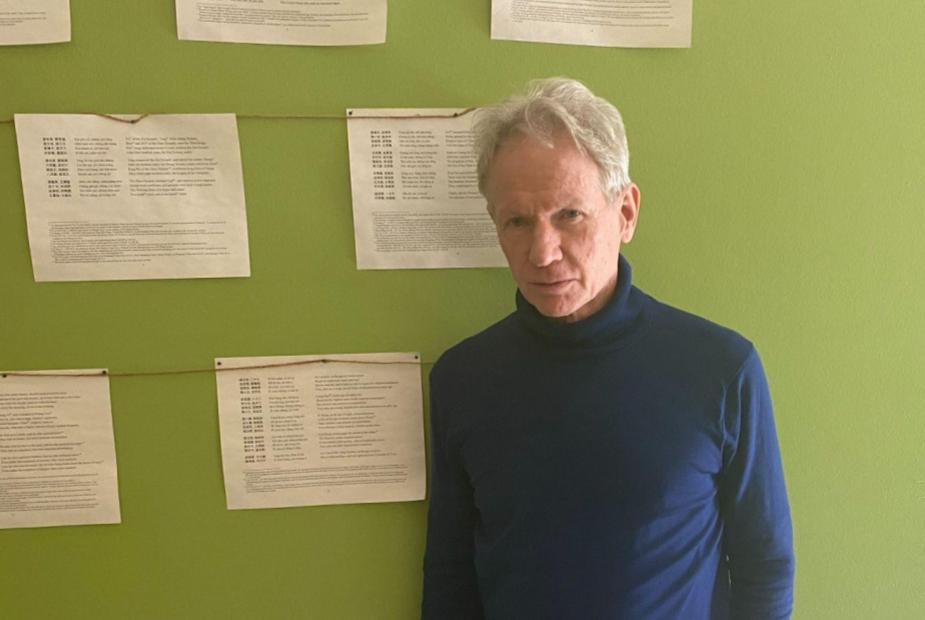

Robert Dillon: Born to Teach

Robert Dillon, a 69-year-old English teacher at Marblehead High School, has lived a life that puts many superhero backstories to shame. From a brief stint as a high-rise window washer in New York City to time spent on construction crews to support his dream of becoming an actor, Dillon has truly seen it all, and the unique perspective that these experiences have given him is evident in his teaching.

Dillon was born in Taipei, Taiwan during the time his father was serving in the United States Central Intelligence Agency. He remained there for two years, at which point his father began work for the US foreign service and moved the family to Puerto La Cruz, Venezuela, where Dillon became infected with a serious tropical disease but eventually recovered. His family went on to spend some time in Turkey, both in Istanbul and Ankara, during which time they frequently traveled back to the United States.

Throughout his childhood, Dillon dreamed of becoming an actor, a passion that led him to spend a number of years pursuing that goal prior to eventually enrolling in university somewhat later than normal. He attended George Mason University, graduating with a Bachelor’s degree in English Literature in less than two and a half years. He went on to earn a Master’s degree, also in English, with the intention of studying for a doctorate in the field at the University of Virginia, but this plan never came to fruition because by this time he was, in his own words, “too old and exhausted.” He explained that he had seen countless educators opt for teaching at the college level in their early years but that he felt he had waited too long.

Instead, Dillon continued pursuing his dream of acting in New York City, during which time he worked the aforementioned jobs as a window washer and construction worker, both positions “that were mostly filled by actors and musicians.” He describes this series of odd jobs as “the ghetto of the talent,” as they were often filled by those in a similar situation to his own, struggling to make ends meet with a dream of Broadway in mind.

Fencing has played an immensely important role in Dillon’s life, often serving as a key creative outlet. He was previously involved in dance, and with his exit from that field, he took up fencing as a replacement. “Fencing was a big part of my life,” he said, “[my wife and I] met at a fencing tournament.” Dillon finds the sport “therapeutic” and “complex enough that mastery demands you integrate many different dimensions, which takes both focus, organization, and discipline.” While in New York City, he often fenced with people who eventually went on to become Olympians. Dillon now serves as the coach of Marblehead High School’s fencing team, passing on his knowledge and love of the sport to the next generation.

Dillon’s father was a successful diplomat with an extensive government career, and his three siblings all hold “very important” jobs in the private sector and in the government. When asked how being surrounded by individuals with so much professional success impacted his outlook, Dillon explains that he always “felt as though I was so far behind everyone, my friends, siblings, the people I grew up with, that I’d never catch them. That made me reluctant to even want to try.” Coming to terms with this hardship has been a “long, hard road,” he says, emphasizing the importance of his father in getting through this difficulty by explaining that “my father very much respects teaching, and he thinks there are too few good teachers.”

Dillon began teaching in 1999 when he moved to Boston with his wife. He decided on English because “it’s something that I actually cared about…and I was good at not just creative writing, but I was also a good literary artist.” He began as a substitute teacher all over the region, eventually earning a job in Boston Public Schools, a role that provided immense joy because “I loved the kids as rough as they were,” further explaining his decision to leave saying that “the politics of Boston are unbearable.”

He went on to work at Swampscott High School under a “very strong English department that taught me a lot.” In all of the classrooms he’s taught in, he has attempted to “prepare the students for higher level thinking” that will be expected of them in college, a daunting task, particularly in the age of social media and technology. “I love the subject,” he explains with regard to why he enjoys teaching, “I didn’t come to teach because I loved kids. It turns out I like the students and young people better than I thought I would… for the well-being and future of this society, we need to not only keep it alive but strengthen and improve [education].”

The biggest challenge facing American education, he said, is that “we would all like to be thought of as intelligent; we aspire to be seen as having qualities and sensibilities, but we don’t necessarily value respect or what’s right.” In an effort to counter this problem in his classroom, Dillon explains that he prioritizes discourse to ensure that students are thinking about what they have been assigned and are able to convey these ideas to one another.

Dillon currently lives in Beverly with his wife. A few months ago his dog Sandy, a black rescue from Louisiana, passed away. “She was a very sad dog” during the first few years she spent with Dillon, “and I don’t know what she’d lost, but it took her a long time to trust us and realize she had a home.” Dillon has had several pets during his life, notably a pet wolf that he found on the street in fourth grade, but he was closer to Sandy than he had been to any previous pet “because she was the most intelligent dog I’ve ever had.” She died from cancer after several months of treatment during which Dillon frequently woke up in the middle of the night to spend time with her, “and we spent a fortune, but I don’t regret it for a minute.”

In 10 years, Dillon would like to still be living on the North Shore and remain deeply involved in the community. “Despite my frustrations, despite waking up at three in the morning and worrying about education in the world and my students, despite the loss of my dog, I am happier than I’ve ever been."

Editor's Note: A previous version of this article suggested that Dillon had spent time in Caracas, Venezuela. It has been updated to Puerto La Cruz, Venezuela, which Dillon explained was a "hardship post" given to younger, inexperienced officers.